Disclaimer: I own eth.

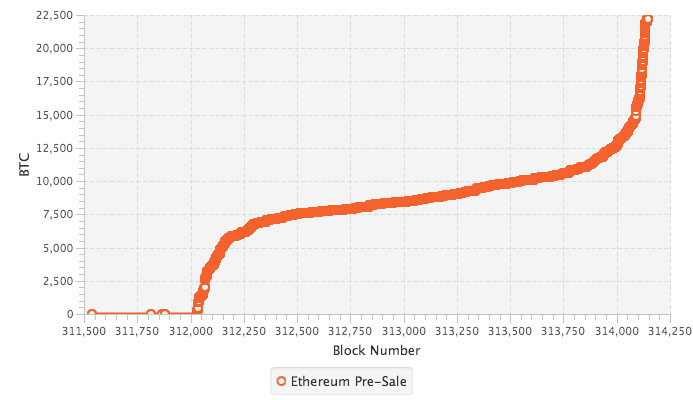

In his latest article Preston Byrne dug up a interesting looking chart that shows the inflow of bitcoins to the ethereum presale in the first two weeks.

The chart looks very smooth, almost too perfect for an uncoordinated effort of several thousand contributions over two weeks, especially compared to charts from other fundraisers like Kickstarter, Swarm or Tezos ICO.

Why should we care about that? Ethereum is currently at risk of being classed as a security. While most people don’t doubt that the ethereum presale was likely a securities issuance, they argue it is now decentralized enough to no longer fit that bill. If it turned out today that the Ethereum Foundation controls a larger supply of ether than they admit and use it to move the market in meaningful ways or even to influence consensus once ethereum has moved to proof-of-stake, that would clearly hurt their decentralization argument. So whether or not there were irregularities in the ethereum presale might be a question of public interest right now. So I set out to understand the formation of this chart a little better.

Confirming the chart

First I confirmed that is indeed from the wallet, which wasn’t hard. For example the Ethereum blog has a post where they review the first 2 weeks of the sale and post the same data.

And my own chart in comparison, over the full presale:

If you want to download the same dataset, go to https://blockchain.info/address/36PrZ1KHYMpqSyAQXSG8VwbUiq2EogxLo2?filter=2# and then click “Filter” -> “Export History”.

The rules of the presale

In order to understand what lead to a graph like this, we need to go back in time and understand the dynamics of the Ethereum presale.

- The sale would go from July 22 until September 2, a total of 42 days.

- The price of ether per bitcoin would be 2000 in the first two weeks, then linearly decline to a final rate of 1337 and stay flat for the last 6 days.

- There was no fixed amount of eth to be sold that investors compete for, instead the eth would be created after the presale is over.

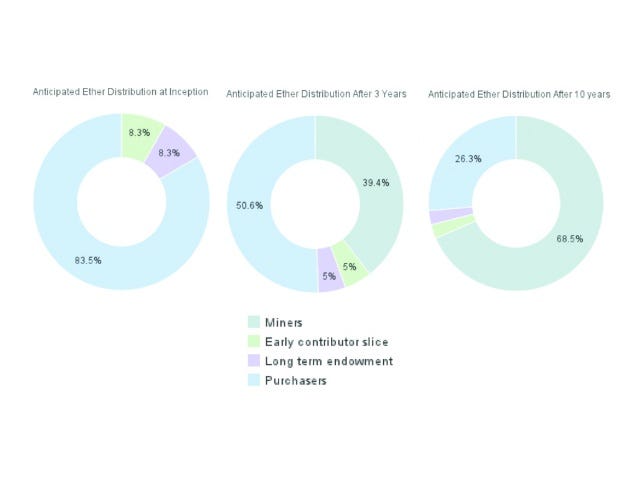

- Then another 19.8% of additional ether would be created and given 50/50 to early contributors to the project and the Ethereum Foundation.

- Yearly inflation through block subsidy would start at 26% for the first year and then decline from there.

This is how they expected the distribution of eth to develop over time:

The players

Given that we know the rules of the presale, what players are there and how do we expect them to behave?

- Speculators: they want to control a large relative amount of ether and hope for demand from the other players only after the sale is over, so they hope to see low interest and then buy as late as possible. At the same time they are price sensitive, so they probably want to buy right before the discount ends and then maybe again before the sale ends.

- Actual users (who buy ethereum as gas, either for using or developing on the platform): they don’t really care when to buy. On the one hand eth gets more valuable to them as more people have already contributed (network effects), on the other hand some of them get incentivized by the early discount.

- Early contributors: here it gets interesting. They know that around 8.3% (~10% of 120%) of all eth created will go to them, so you can think of it as an 8.3% bonus on every purchase. At the same time they benefit from getting others to contribute as much as possible (like an affiliate deal, they receive 8.3% from each purchase). So we would expect them to participate generously and probably early, to spin up demand and signal to the other players.

Insiders

Because they are the key to this analysis, this fourth player deserves her own paragraph. An insider would be someone who colludes in some way or form with the Ethereum Foundation to gain an unfair advantage over others.

Goals to such collusion could be:

- to signal (“fake”) demand to other players to raise more money

- to make additional short- or midterm profits by selling on the open market (even cornering it)

- to secretly control a larger share of the monetary base, either to manipulate prices or influence consensus in a PoS system

What allows all three options to work in the first place is that an insider and the Foundation could be sharing the same bankroll. So whatever money the insider spends, is not really gone but can be returned to him by the Foundation, greatly reducing the cost to him. I illustrated that dynamic here:

In step 1, we see an honest user buying 2000 eth for 1 btc. He is +2000 eth but -1 btc and the foundation is +1 btc and +200 eth (because of the free 10% they are printing). The foundation+insider coalition controls 200 eth (10% of the supply) and 2 btc.

In step 2, we see that an insider that spends the same 1 btc, gets the same 2000 eth but the 1 btc never leaves his shared bankroll with the foundation. The foundation+insider coalition now controls 2400 eth (55% of the supply) and 2 btc. They just printed money for free.

There are three caveats to this situation:

- The coalition needs some Bitcoin to begin with.

- There might be a cost associated to sharing a bankroll, for example a tax on whatever money flows back from the foundation to the insider.

- There could be an additional cost if their collusion ever came out.

These aspects make the collusion a little more costly, but by no means unprofitable. So just based on these incentives, we expect that collusion is likely to happen. Maybe not in this case, but given a large number of dice rolls (ICOs) the dice will come up 6 (an unethical founding team) a reasonable amount of the time.

The reality check

In summary we expect a big spike in the beginning as well as towards the end of the discount. Apart from that, there should be a noisy baseline of demand from actual users.

If we compare these expectations to the actual demand, we can that they fit the chart (taken from here):

There was a big spike in the beginning and another one right before the end of the discount (red line). The rest of the time daily demand was surprisingly stable, with another small bump towards the very end.

There is still the question why the graph looks so damn smooth. So I rearranged the transactions in two more ways.

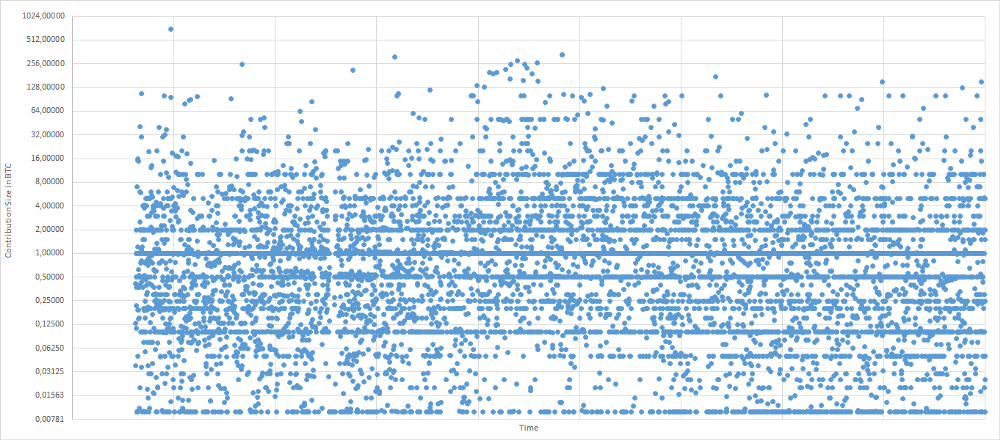

By size in BTC, over time

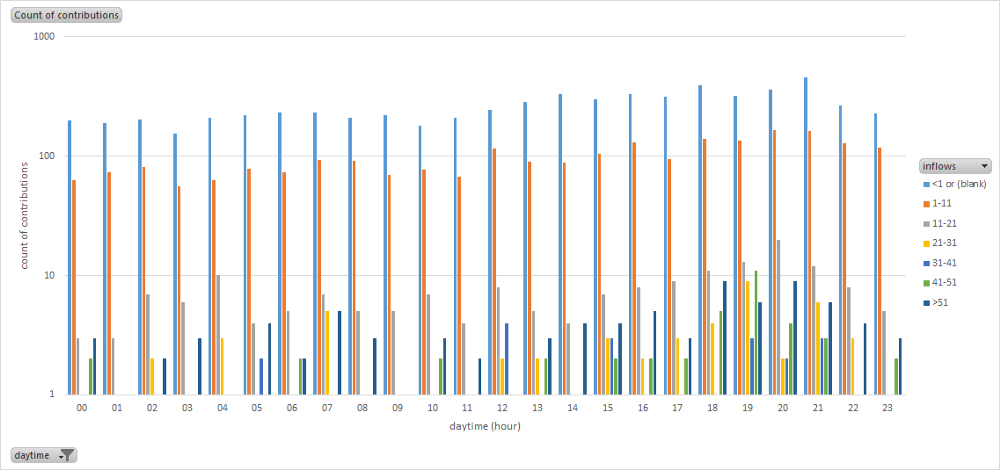

And grouped, per hour of the day (for example blue is the count of all transactions between 0–1 BTC, orange between 1–11 BTC etc.)

I think neither chart reveals much more than that transactions have been coming in a steady flow, but I included them anyway.

Conclusion

We set out to answer if there was inside-investing or other irregularities in the Ethereum presale. We looked at the rules of the presale and formulated strategies for all actors. The shape of the chart (as compared to other charts referenced by Preston) can be explained by these strategies. It’s hard to draw further conclusions from the dataset because, even though it is very rich, in the end we don’t know the identities behind the transactions. In particular very stable inflow of small transactions is still a mystery to me. If someone wants to dig deeper, I think looking for connections between the individual accounts that contributed would be the next logical step.

We also showed that the spike in the beginning, can be explained with incentives for two groups.

- If you were an Ethereum early contributor, you know that you will receive an 8.3% bonus on whatever money you put in. You also want Ethereum to raise as much money as possible, so you probably buy in very early to signal demand to the group who is thinking about buying eth as a commodity.

- If you are an insider, you have all the incentives of the early contributor plus the added incentive that you can get (part of) your money back from the foundation. You might also have the (more far-fetched?) incentive to secretly control a larger fraction of the money supply and influence consensus or price movements.

We are not too worried about group 1, the early contributors, as long as they are not also in group 2, the insiders. But we have shown that insider-investing is incentivized by ICOs in general and the structure of the Ethereum presale in particular. Whatever is so clearly incentivized is most likely happening in the real world. If not in this case, then surely in other ICOs. I am not alleging that it happened, but people should probably keep in mind the existence of this unholy dynamic in the future.

So should we be worried about the long-tail risk of the Ethereum Foundation secretly controlling a larger share of the money supply? I find it hard to say from a standpoint of price-manipulation, but I’m fairly sure that, if there ever was a time window where they could have controlled consensus, that window is now closed because they missed the transition to PoS by several years and inflation has caught up with them.